Benedictine Monasticism

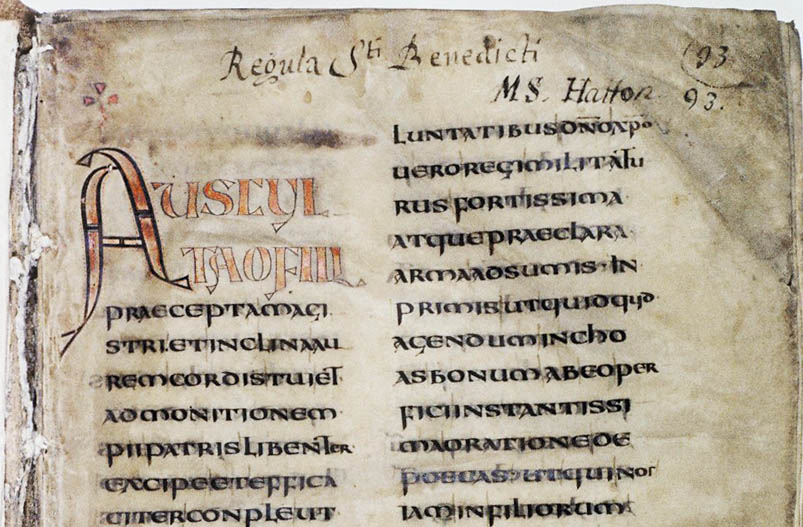

"Listen carefully, my son, to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.” —RB Prologue

With this introduction to his Rule, St. Benedict calls the brother to the basic stance of his vocation: a monk is someone who inclines his ear to the Divine Voice, who opens his eyes to the Light of Christ.

The word "monk" derives from the Greek monos, meaning "alone." The monk or nun’s single-hearted aim is to seek union with God. In order to fulfill this, the monastic stands alone, apart from the world. In his Rule, St. Benedict, an heir to both the early eremitical desert tradition of Egypt and the cenobitic life initiated by later monastic founders, combined the virtues of solitude—of silence, contemplation, and the singular search for God—with a life of fraternal charity lived in community with others who share the same ardent search for God. Always, our teacher and Lord is Christ; a monk or nun can thus be defined as someone whose "life is hidden with Christ in God" (Col 3:3), in community with others, according to a rule, under the guidance of an abbot or abbess.

St. Benedict’s provided a plan for monastic life and prayer that, fifteen centuries later, remains the most widely used in the world. Because the Rule is rooted in the Gospel and is characterized by a pervading kindness, clarity, and common sense and adaptability, it has remained fruitful in all ages and all lands. Both practical and spiritual, it covers such varied topics as the celebration of the liturgy, silence, humility, the measure of food and drink, reverence at prayer, the election of the abbot, and the reception of guests.

Benedictine Vows

The three vows of every Benedictine professes are stability, conversio, and obedience.

Stability means remaining in the particular monastic community in which one has made solemn profession. On one level, this suggests rejecting the aimless, headlong rush from one distraction to another that characterizes so much of modern life; it means accepting who one is—a finite creature, loved by an infinite God; it means remaining on stable course in the monastic life, belonging by vow to the particular monastic “family” which one joins through solemn profession.

Conversio, or conversatione morum, translated as “conversion of manners” or “conversion of life,” is a vow to be a nun: to take on the “mores”—Latin for “customs, values and behavior,” the “ways, conduct and character”—of a nun as lived in one’s particular monastery. The conversion from living one’s established personal way into a communal way is not easy in our culture of self-directed individualism. Pope Francis often speaks about this trend in our modern society.1 Conversio never ends; each monk and nun begins again each dawn, offering his or her life up afresh to Our Lord.

Obedience means, above all, obedience to the abbot, who, St. Benedict tells us “is Christ’s representative, called by His name: ‘You have received the spirit of the adoption of sons, whereby we cry, Abba, Father’” (Rm 8:15). Obedience for St. Benedict is a “bonum”—a “good”—that is extended also to one’s fellow community members. In imitation and union with Christ, who was “obedient even unto death” (Phil. 2:8), mature obedience enables the monastic to center his or her life in God rather than self. This total gift of self to God in love is an act of faith and trust in him is a “Yes” and an abandonment to his will, with the assurance that he will not fail us.

The Rule also establishes three activities that comprise day-to-day monastic life: prayer, work, and lectio divina or sacred reading.

Prayer

Every monk and nun engages in private prayer, an intimate conversation with God, a loving expression of praise, adoration, thanksgiving, and petition. However, the central form of prayer in Benedictine monasticism is not private but corporate: the Divine Office, also known as the Liturgy of the Hours. St. Benedict calls this time of prayer the opus Dei or “work of God”—and truly it is the main work of the monk and nun in tribute to God, and, conversely, it is God’s own work, the way in which He continues to speak to the world through the words of Holy Scripture that comprise each Hour. Of the opus Dei, Benedict wrote in his Rule “We believe that the divine presence is everywhere.... But beyond the least doubt we should believe this to be especially true when we celebrate the Divine Office."

Work

St. Benedict explains in his Rule that “idleness is the enemy of the soul.” He therefore counsels “specified periods for manual labor” for all monks and nuns. Monastic work can include such activities as agriculture, arts and crafts, intellectual work and greeting of guests, as well as the day-to-day tasks of any household. Whatever the activity, the work becomes itself a form of prayer, a way of offering one’s energies to God for the completion of his Kingdom.

Lectio Divina

Every monk and nun devotes a part of each day to sacred reading of Scripture and the early Fathers of the Church, in order to hear the voice of God as expressed in revealed texts. This ancient practice of prayerful reading, in which the inspired words are pondered over, committed to memory, opens the monk or nun to contemplative prayer.

After St. Benedict

St. Benedict died c. 547 A.D. In the centuries since, his Rule spread throughout the world and, in time, inspired other monastic movements, most notably the Cistercians and Trappists. But despite development and diversity, the Benedictine way remains fundamentally unchanged. As one monk has said, “a sixth-century monk should feel at home in a twenty-first century monastery.”

LINKS

- The Holy Rule:

- The Rule of St. Benedict in PDF form

- The Rule of St. Benedict An index to texts online and bibliographies

- Benedictine Spirituality:

- A Twenty Minute Noviciate (Six Hallmarks of Benedictine Spirituality) by Fr. Harry Hagan, OSB

FURTHER READING

- The Holy Rule:

- RB1980: The Rule Of St. Benedict in English, Timothy Fry, OSB, Translator (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1981)

- Benedict's Rule: A Translation and Commentary, Terrence Kardong, OSB, (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1996)

- Esther De Waal, A Life Giving Way: A Commentary on the Rule of St. Benedict, (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1995)

- Benedictine Spirituality:

- Columba Marmion, OSB, Christ the Ideal of the Monk, (St. Louis: Herder, 1926)

- Esther De Waal, Living With Contradiction: Reflections on the Rule of St. Benedict, (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1989)